|

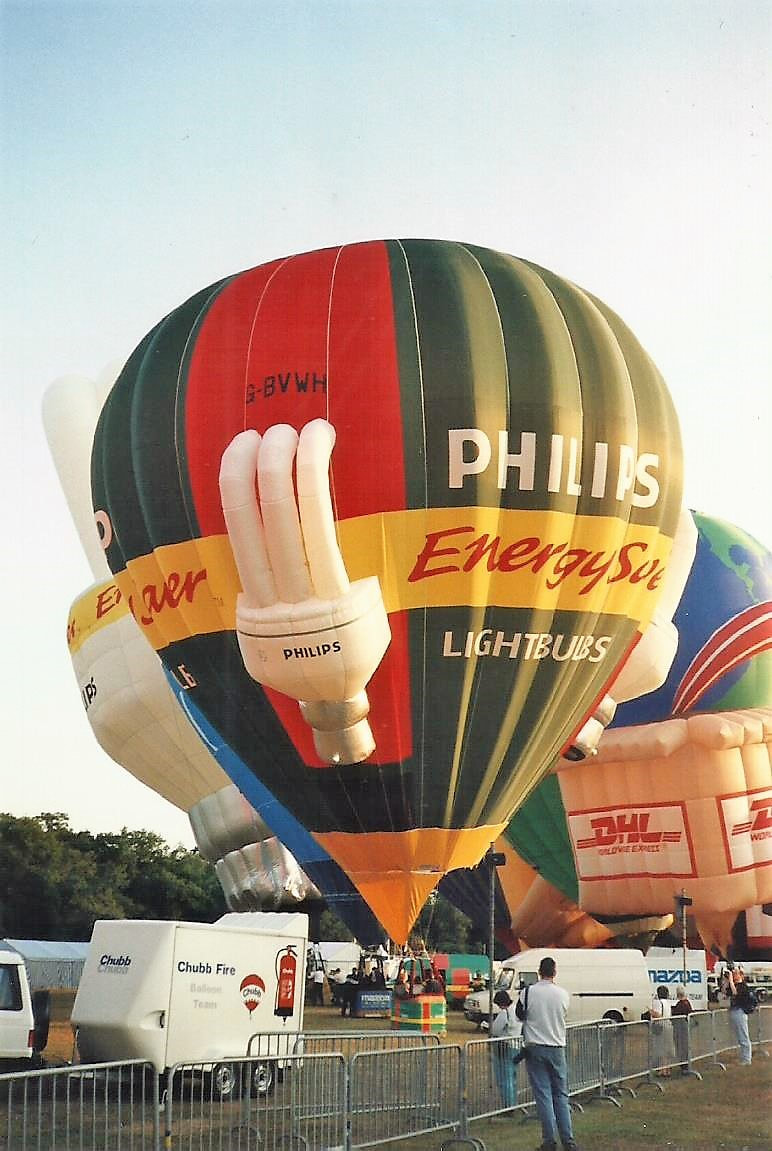

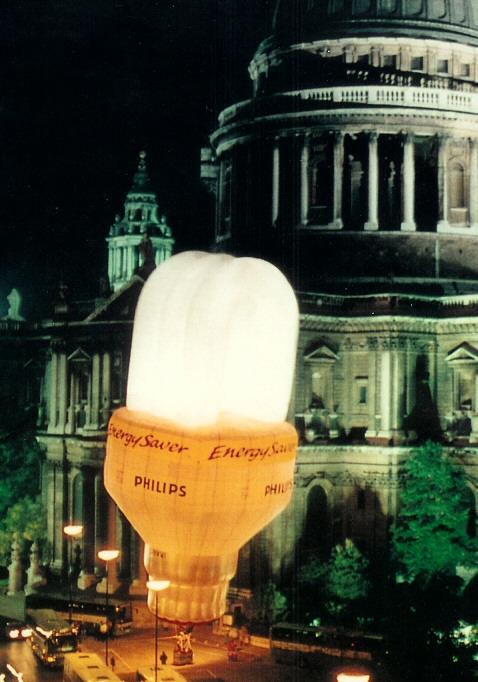

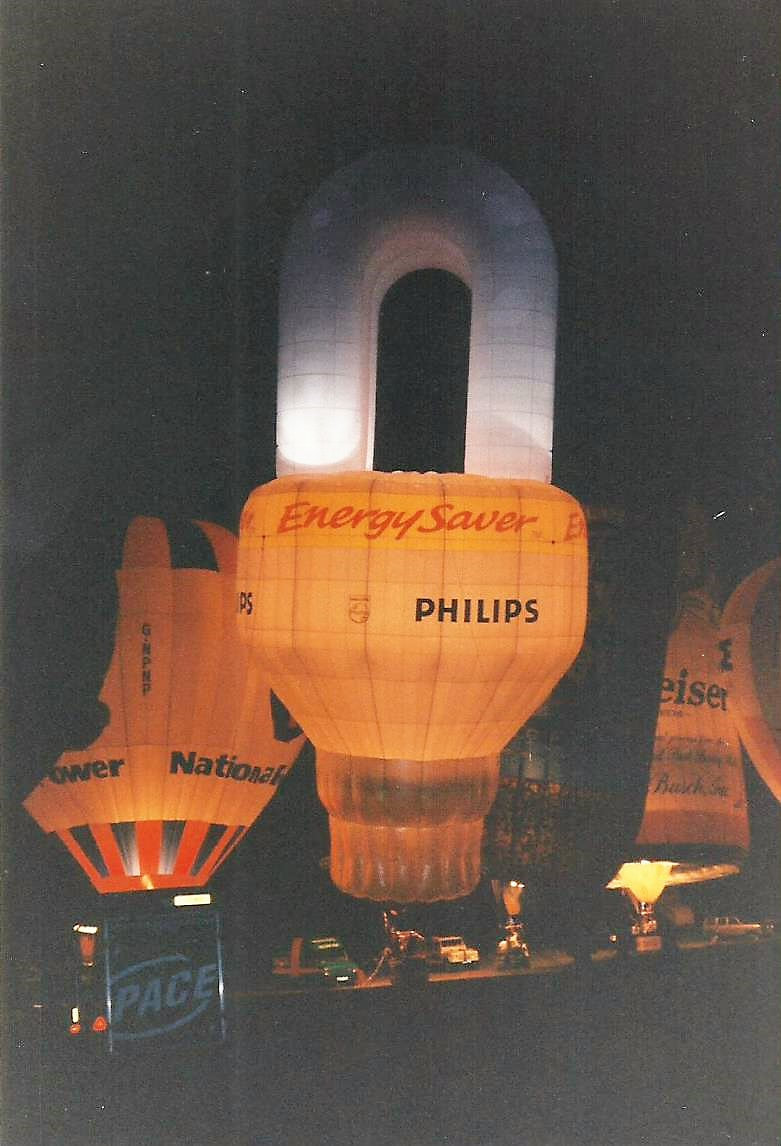

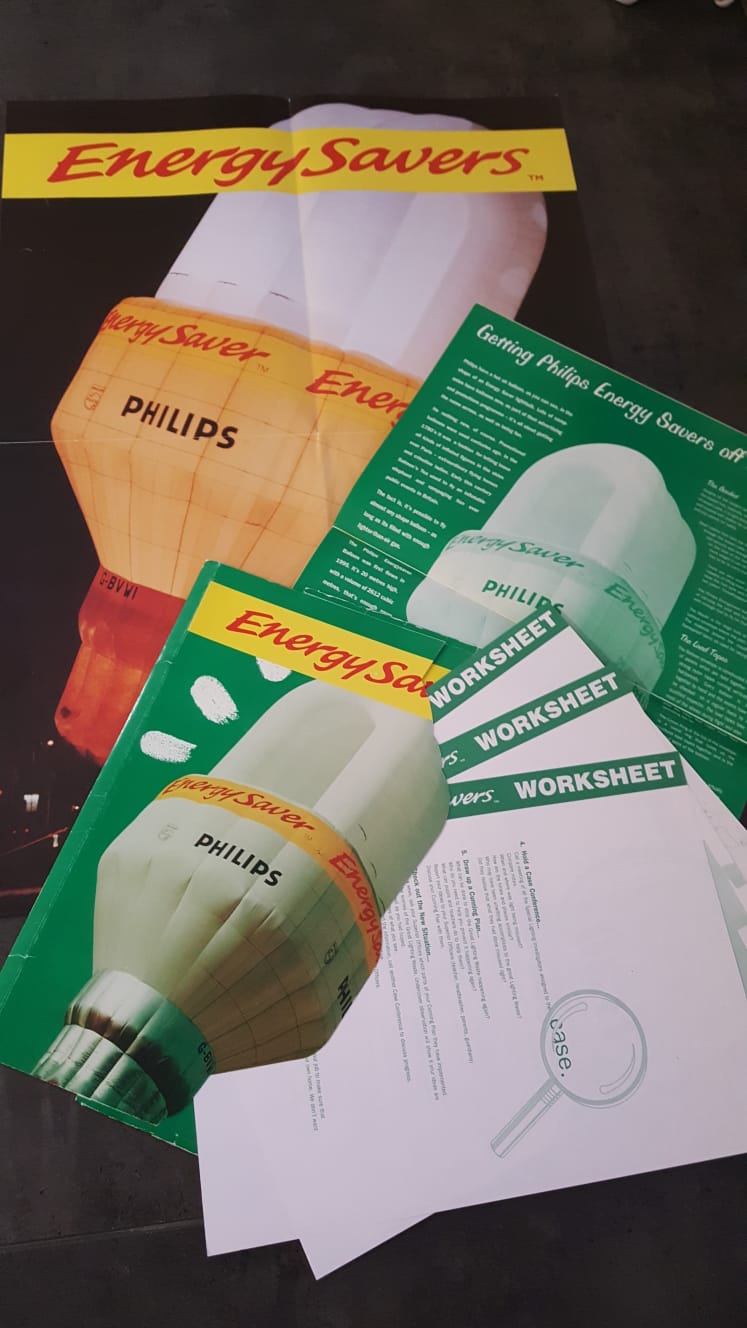

Next up in our series of special shape blogs is the Philips light bulb built in 1995! Mark Lockwood, Creative Director at Virgin Airship & Balloon Company during the 90s, tells us about the complex lighting process of the 149ft tall special shape and standard add-on 90, unveiling to the Philips team in London, an impressive tether outside St Paul's Cathedral and flying from the Southampton Balloon Festival. You can also watch YouTube video on the build of the light bulb and find recent photos of inflations in Ireland further down. Many thanks to Mark for writing. We hope you enjoy! Since Thomas Edison first enlightened a select group of guests gathered in a blacked-out room in 1878, the world emerged from dim flickering odorous candle and gas lamp lit darkness into the bright glare of incandescent tungsten filament bulbs. We have bathed in their warm glow for years however their thirst for electrical power, and our blind need to be able to see in the dark, led to a proliferation of non-sustainable fuel hungry, coal and gas munching power stations, belching out tons of carbon dioxide and other non-desirable side products into the atmosphere, clogging up our lungs, warming the planet and incurring the wrath of an angst ridden sixteen year old teenager in Sweden! But there was an alternative. Discovered and developed almost at the same time as Edison’s vacuum tube, the ability to excite a bunch of mercury and phosphorous atoms in a tube with an electrical current to provide a brighter, cleaner, less power hungry, fluorescence became mired in a series of patent disputes and didn’t shine its light from under a bushel until the early 1920s. When it did, it revolutionised the requirement to light the increasingly vast industrial enclosures we needed to feed the consumerist society we were becoming. Night became day as production lines went from limited daylight hour diurnal operations to round the clock churning output to feed the growing need for cars, washing machines and cuddly toys. All under the daylight glare of the ubiquitous fluorescent tube. Our greed and need for increasing amounts of electricity became an exponential equation as the technological revolution of the late 1990s kicked in. Homes and businesses demanded increasing numbers of amps and watts to power the proliferation of home computing, Hi-fi, Wi-fi, gaming, appliance based lifestyle we had become accustomed to in a very short period of time. All this demand had an associated cost as our electricity bills burned holes in monthly domestic budgets and we, the consumer, looked at ways to bring them back from the stratosphere. The problem was the traditional fluorescent tube did not fit into bayonet equipped lamps, ceiling rose fittings and chintz covered bedside lanterns. I don’t actually remember when I first met Nick Mallinson from Philips Specialist Lighting Division; it may well have been at a seminar or even a random call one day. Nick was the recently appointed marketing manager for a revolutionary new product that Philips boffins had been cooking up in a backroom in Holland. It was a fluorescent light…in a format that would fit into the majority of standard light fittings, but it looked a little weird to the consumer eyes and he had a problem with early adoption despite the outstanding energy saving advantages it offered. Here was a bulb that operated with only 10 Watts and produced the same output as a standard 60 Watt electricity guzzling incandescent one. Its full name was a ‘Phosphorescent Low Energy Tube’, abbreviated to PLET. The numbers were pretty impressive. If every household in the UK adopted just one energy saving PLET bulb, the UK would not need to build another 9 power stations over the next 10 years! An innovative product needed an innovative marketing solution. Visiting the Philips offices in south London, I was sworn into secrecy and taken into an extremely well-lit Aladdin’s cave where they displayed all the highly specialised bits and bobs in their arsenal. From tiny very early concept LED lights for point of sale, to amazing programmable fibre optic displays, right up to the landing and runway lights for airports and deep ocean underwater units for use in seabed exploration. Not being a ‘lampy’ but having had my day hauling and setting up huge stage lighting rigs, it was quite enlightening (sic.) Being presented with the PLET bulb for the first time, my head started running some preliminary numbers regarding available volume against active lift and weight. My first impulse was to look at a way of enclosing the space withing the curved tubes and creating a more viable hot air space at the top of the balloon, but this immediately detracted from the unique shape of the thing. I even considered a clear fabric either side of the tubes but the materials available at the time were a semi opaque finish and, from some experiments already carried out, yellowed, and increased their opacity very quickly with heat. This was potentially a ‘3 Jack’ problem, based on the number of shots of Jack Daniels finest ‘Thought Provoker’ needed to solve a particularly tricky problem. Returning to base with 2 precious rare sample bulbs, one was immediately dispatched to the studio and into the hands of wizard artist and designer Mark Urey. The other went to Cameron Balloons and into the hands of designer Steve Wallace. Like me, his initial reaction was a sucking of air over teeth and asking if the void could be somehow compromised. Once we unanimously agreed this was not an option, out came the calculators and it was quickly established that the combined lift available from the tubes and the main body of the bulb would actually be sufficient without it becoming an inoperable beast. Then I threw them the curve ball that I wanted it to light up like the real thing. In free flight. I could hear the face palms and rending of hair from my office in Telford! Philips were adamant that the colour temperature of the internal lighting should exactly match that of the actual bulb, which created some huge logistical problems as the only lamps suitably powerful enough to produce this were big, heavy, hot and cost £1000 each, a huge amount back in the 1990s, and only had working life of about 100 hours. They also slurped a vast amount of Wattage which meant providing a generator power source in the basket. We had already gained a lot of experience doing this from the Virgin Galactic Airlines UFO balloon, built for Branson’s April Fool’s Day stunt over London, but it was still fraught with problems. With the technicians at Philips, we worked out that a 3.5KVa generator would give sufficient running power and there was a neat little Honda unit on the market that fitted the bill precisely. This was mounted with the exhaust venting through the basket foot hole and a metal heat shield put around the opening. The lamps would need a much larger charge on start-up, which would need a series of ballast units mounted to a board built into the basket between two of the fuel tanks. The next issue was the power getting to the lamps themselves as the normal cable required was extremely heavy duty and plastic coated, a problem when exposed to the extreme heat inside the envelope. Head office in Eindhoven sent over a hideously expensive roll of experimental cable that used a conducting fluid, instead of the more traditional copper wire, and featured a heat resistant silicon armoured coating. Apparently, this stuff was only being used in military applications. The build was fully underway at Cameron’s together with a standard shape 90,000 cubic foot back up envelope. I decided to blister inflate the bulbs from the side of this and, as they were much smaller, we were able to use a car battery operated internal lighting system for these. As the tubes were completed on the sewing room floor, we arrived with the technical team from Philips and later experimented with the lights during a cold air inflation for the first time. It quickly became apparent that the lamps were super delicate, and we would need to protect them from the rigours of ground handling and inflation/deflation. Steve Wallace came up with a simple mounting pad that protected the lamp to a degree but, most importantly, avoided them melting the balloon fabric. Delivery time approached and we took the balloon all the way up to Birkenhead and test inflated it indoors at the Cammell Laird shipyard, a regular test space that was big enough to inflate most taller than average special shapes. There were a few tweaks and some problems to iron out and then we were ready to unveil the balloon to the Philips management team in a park close to their offices. Obviously, this needed to be after dark and pilot Graham Dorrell and the team were duly dispatched to light up their lives. Having only inflated in a perfectly calm environment, one of the first things we found with the shape was any wind passing through the open space under the arching tubes, created an oscillating low pressure area that built up into a harmonic swing and caused the envelope to spin. Wildly. The launch was very successful and highly impressed the top brass but the tether was brought to an abrupt end after they left when the balloon spun itself around so many times it closed the mouth and tied all the flying wires into what appeared to be a single steel hawser. The traditional single crown line was not sufficient to stop the rotation, so we immediately modified and added 2 additional strengthened ‘D’ ring points either side of the tubes and used 2 handling lines when tethering. This gave the crew the ability to hold the envelope stable and stop the wild swinging but proved hard on their arms. The Energy Saver Light Bulb was the star of that years Bristol Balloon Fiesta Night Glow, standing proud and bright in the middle of the arena surrounded by all the other standard shapes. Used extensively over the next 3 years, there were one or two media opportunities that popped up. In conversation with Nick one day I found out that the specialist lighting division was providing all the architectural lighting for the newly restored and renovated exterior of St. Pauls Cathedral in the City of London. Co-incidentally I knew the official architect for the cathedral, Sir William Whitfield, and with his contacts and help from the office of the Mayor of the City of London, we were able to secure a tethering space in front of the building, something that had never been done before. Getting police permits and permissions for photography proved a lot harder but with perseverance and doggedly not taking ‘No’ for an answer, we waited for a suitably calm weather slot. It came up and everything had to be mobilised at extremely short notice. The police barriered off the space we were allocated and provided a whole squad of officers to patrol, and the inflation process could begin. Our photographer had found a perfect vantage point in the offices of American Express that overlooked the site, however getting an after hours permit was possibly the hardest thing we had to do. Security escorted him to the closed and deserted CEO’s office and the picture window overlooking the site and watched him like a hawk for the whole 30 minutes needed to get the shot. It was worth it! I personally had the pleasure of flying the 90 standard shape one year from Southampton Balloon Fiesta and it turned out to be an interesting flight for the press I had on board. The wind was a north easterly and carried us from the Common over the centre of the city but unfortunately directly towards the estuary. The New Forest on the other side of the water was strictly a no landing zone so I had to make a positive pilots decision and descended upon the container cargo depot, dodging huge light poles, cranes and stacks of shipping containers to a gentle landing on the tarmac apron. A memorable flight! Above: another exclusive, this is the schools resource pack we sent out as part of the educational process. We did a limited number of school visits but produced and distributed these in their thousands. Both balloons still exist. The light bulb is in the careful hands of Malcolm White, who is working on a new LED lighting solution that will only require a battery operated power source and resides in Ireland, whilst the standard shape is with the Balloon Retirement Home. Most importantly, energy saving light bulbs and the new generation of LED based lamps are now the predominant source of lighting around the world and I am proud to have been at the spearhead of this movement and the global benefits it has brought to the environment. Watch BBC 2 documentary about the development and making of the balloon on YouTube. Thanks to Ballooning Pictures UK and Malcolm White for supplying many of the photos in this blog. Here are some extra photos of a more recent inflation in Ireland. Read more about special shape balloons on MJ Ballooning You can read more from Mark about many of his other special shape creations including Action Man, Bic Chick, Monster.com and Sonic the Hedgehog by following this link. Look out for a very special one coming soon...

Comments are closed.

|

BlogWelcome to MJ Ballooning's blog! Read about local goings on, special shapes and more.

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

|

- Home

- Our Balloons

- 2024 Season

- Special Shapes

-

Gallery

-

Bristol Balloon Fiesta

>

- 2023 Fiesta

- 2022 Fiesta

- 2021 Fiesta

- 2020 Fiesta

- 2019 Fiesta

- 2018 Fiesta

- 2017 Fiesta

- 2016 Fiesta

- 2015 Fiesta

- 2014 Fiesta

- 2013 Fiesta

- 2012 Fiesta

- 2011 Fiesta

- 2010 Fiesta

- 2009 Fiesta

- 2008 Fiesta

- 2007 Fiesta

- 2006 Fiesta

- 2005 Fiesta

- 2004 Fiesta

- 2003 Fiesta

- 2002 Fiesta

- 2001 Fiesta

- 2000 Fiesta

- 1998 Fiesta

- 1990 Fiestas >

- 1990 Fiesta

- 1990s Night Glows

- Late 1980s

- 1988 Fiesta

- 1983 Fiesta

- 1981 Fiesta

- Mixed Fiesta Photos

-

2022 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 12/01/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/01/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 16/01/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 23/01/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/01/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 11/02/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/03/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/03/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/03/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 20/03/22 - Orange Inflation at Ashton Court PM

- 24/03/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/04/22 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 08/04/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 09/04/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/04/22 - Maize Field AM

- 10/04/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/04/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/04/22 - G-LIPS Flight from Ashton Court PM

- 15/04/22 - Special Shape Tether at Ashton Court

- 15/04/22 - G-LIPS Flight from Maize Field PM

- 16/04/22 - G-LIPS Flight from Maize Field PM

- 18/04/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/04/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 28/04/22 - Newbridge PM

- 29/04/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 30/04/22 - Maize Field AM

- 30/04/22 - Ashton Court Tether

- 30/04/22 - G-LIPS Flight from Ashton Court PM

- 05/05/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/05/22 - Maize Field PM

- 08/05/22 - Maize Field Tether

- 08/05/22 - Maize Field PM

- 12/05/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/05/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/05/22 - Maize Field PM

- 19/05/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/05/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/05/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 27/05/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/05/22 - Maize Field AM

- 28/05/22 - Bath Balloon Fiesta | Royal Crescent PM

- 29/05/22 - Bristol Balloon Tether at Ashton Court AM

- 13/06/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/06/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/06/22 - Flight from Ashton Court AM

- 14/06/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/06/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/06/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 16/06/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/06/22 - Orange Inflation at Ashton Court PM

- 21/06/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 22/06/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 22/06/22 - Maize Field PM

- 22/06/22 - Newbridge PM

- 23/06/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 03/07/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 05/07/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/07/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/07/22 - Keynsham PM

- 09/07/22 - Maize Field AM

- 09/07/22 - Keynsham AM

- 09/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 10/07/22 - Maize Field AM

- 10/07/22 - Special Shapes at Ashton Court PM

- 11/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/07/22 - Coffee Jar Flight from Norton St Philip PM

- 20/07/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 26/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 28/07/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 29/07/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/08/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/08/22 - Maize Field AM

- 06/08/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/08/22 - Alien Inflation at Newton St Loe AM

- 07/08/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/08/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/09/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/09/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/09/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 18/09/22 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 19/09/22 - Keynsham PM

- 21/09/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/10/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 08/10/22 - Ashton Court PM

- 19/11/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/12/22 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/12/22 - Ashton Court Tether PM

- 16/12/22 - Ashton Court AM

-

2021 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 02/01/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 27/02/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/03/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 08/03/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 30/03/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/03/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/03/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/04/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/04/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/04/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/04/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/04/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/04/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 16/04/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/04/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 17/04/21 - Maize Field PM

- 18/04/21 - Maize Field AM

- 18/04/21 - Maize Field PM

- 19/04/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 20/04/21 - Maize Field PM

- 26/04/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 27/04/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/05/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/05/21 - Ashton Court Tether AM

- 07/05/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/05/21 - Maize Field Tether

- 17/05/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 27/05/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 27/05/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 27/05/21 - Maize Field PM

- 28/05/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/05/21 - Maize Field PM

- 30/05/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 31/05/21 - Maize Field AM

- 04/06/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/06/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 08/06/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 09/06/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/06/21 - Bath Balloon Fiesta | Inglescombe Farm PM

- 13/06/21 - Bath Balloon Fiesta | Glasshouse Playing Fields AM

- 13/06/21 - Bath Balloon Fiesta | Glasshouse Playing Fields PM

- 14/06/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/06/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/06/21 - G-LIPS Tether at Ashton Court PM

- 17/06/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/06/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 23/06/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/06/21 - G-DIPI Tether at Ashton Court PM

- 30/06/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/07/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 02/07/21 - Poplar Insulation Tether at Ashton Court AM

- 02/07/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/07/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 09/07/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/07/21 - Keynsham PM

- 14/07/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/07/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 15/07/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 16/07/21 - Keynsham PM

- 17/07/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/07/21 - Maize Field PM

- 18/07/21 - Maize Field AM

- 18/07/21 - Special Shape Tether at Ashton Court PM

- 19/07/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/07/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 21/07/21 - Maize Field PM

- 22/07/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 25/07/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/07/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 01/08/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 01/08/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/08/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 12/08/21 - Dundridge Park AM

- 22/08/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/08/21 - Maize Field PM

- 25/08/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 27/08/21 - Maize Field AM

- 03/09/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 04/09/21 - Maize Field PM

- 05/09/21 - G-LIPS Flight | Maize Field PM

- 12/09/21 - Maize Field AM

- 14/09/21 - Keynsham PM

- 14/09/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 15/09/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/09/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/09/21 - J&B Bottle Special Shape Tether AM

- 20/09/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 20/09/21 - Maize Field PM

- 21/09/21 - Keynsham PM

- 21/09/21 - Oakhill Recreational Ground, Radstock PM

- 06/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/10/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 08/10/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 09/10/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 10/10/21 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 10/10/21 - Keynsham PM

- 11/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/10/21 - Keynsham PM

- 13/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/10/21 - Keynsham PM

- 17/10/21 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/11/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/12/21 - Ashton Court AM

- 26/12/21 - Ashton Court AM

-

2020 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 20/01/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/01/20 - Galleon Special Shape Tether AM

- 27/05/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/05/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/06/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/06/20 - Henbury Tether PM

- 24/06/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 24/06/20 - Henbury Tether PM

- 07/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 11/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 11/07/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/07/20 - Maize Field Tether

- 12/07/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/07/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/07/20 - G-GCCC Flight | Bristol County Ground PM

- 21/07/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 29/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 29/07/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 30/07/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/07/20 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 30/07/20 - County Ground PM

- 02/08/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/08/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/08/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/08/20 - Henbury Night Glow

- 09/08/20 - Maize Field PM

- 27/08/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/08/20 - WRBBAC Flyout | Timsbury PM

- 31/08/20 - George Brazil Airship | Havyatt Green AM

- 31/08/20 - Maize Field PM

- 01/09/20 - Sky Orchestra | Ashton Court PM

- 06/09/20 - Key Worker Flight over Bristol AM

- 10/09/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 11/09/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/09/20 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 15/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/09/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/09/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/09/20 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/09/20 - Bristol Balloon Tether | Ashton Court PM

- 29/09/20 - Wallace & Gromit Rocket Launch | Lloyds Amphitheatre AM

- 29/09/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 11/10/20 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/11/20 - Ashton Court AM

-

2019 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 27/02/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 27/02/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/03/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/03/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 24/03/19 - Maize Field AM

- 24/03/19 - Upper Swainswick AM

- 25/03/19 - Maize Field PM

- 26/03/19 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 26/03/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 27/03/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/03/19 - Wraxall PM

- 29/03/19 - G-UWEB Tether | Ashton Court PM

- 30/03/19 - Keynsham PM

- 01/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 11/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 12/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 19/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 19/04/19 - Maize Field PM

- 20/04/19 - Maize Field AM

- 20/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 20/04/19 - WRBBAC Flyout | Maize Field PM

- 21/04/19 - Maize Field AM

- 21/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 21/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 21/04/19 - Maize Field PM

- 23/04/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 28/04/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/04/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 30/04/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/05/19 - Maize Field AM

- 05/05/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 06/05/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 10/05/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/05/19 - Maize Field AM

- 12/05/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 12/05/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/05/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/05/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 24/05/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/05/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/05/19 - Bath Balloon Fiesta AM

- 31/05/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/06/19 - Shirehampton PBA Club Fun Day

- 06/06/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 09/06/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 18/06/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/06/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/06/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/06/19 - G-NORG Airship in Ashton Court AM

- 25/06/19 - Flight from Maize Field PM

- 02/07/19 - Flight from Maize Field PM

- 03/07/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 04/07/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/07/19 - Longwell Green Tether PM

- 05/07/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 05/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 06/07/19 - Flight from Ashton Court AM

- 06/07/19 - Lawrence Weston Tether at LDubstock

- 07/07/19 - Maize Field AM

- 07/07/19 - Flight from Ashton Court PM

- 08/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 09/07/19 - Flight from Ashton Court PM

- 10/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/07/19 - Maize Field PM

- 14/07/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 15/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/07/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 24/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/07/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/08/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 01/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 02/08/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/08/19 - Maize Field PM

- 13/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/08/19 - Pettefords Tether at Nailsea

- 20/08/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 20/08/19 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 21/08/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/08/19 - Flight from Maize Field PM

- 23/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/08/19 - Maize Field AM

- 25/08/19 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 25/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/08/19 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/09/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/09/19 - Keynsham AM

- 07/09/19 - Maize Field PM

- 08/09/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 08/09/19 - Timsbury Flyout PM

- 10/09/19 - Ashton Court AM

- 18/09/19 - Keynsham PM

- 19/09/19 - Maize Field PM

- 16/11/19 - G-BIRE Tether at Ashton Court

-

2018 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 06/03/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/03/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/03/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/03/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 05/04/18 - Test Inflations AM

- 19/04/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/04/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/04/18 - Maize Field PM

- Balloon Flight | 21/04/18 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 03/05/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 03/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/05/18 - Chubb Special Shape Inflation | Ashton Court AM

- Balloon Flight | 04/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- Balloon Flight | 05/05/18 - Maize Field AM

- 05/05/18 - Maize Field PM

- 05/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 06/05/18 - Maize Field AM

- 06/05/18 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 06/05/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/05/18 - Maize Field PM

- 06/05/18 - Balloons over Bristol PM

- 07/05/18 - Maize Field AM

- 07/05/18 - Chew Magna Flyout PM

- 08/05/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 10/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/05/18 - Maize Field AM

- 12/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/05/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/05/18 - Portway Tether AM

- 14/05/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 17/05/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 25/05/18 - Bath Balloon Fiesta PM

- 02/06/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/06/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 03/06/18 - Maize Field PM

- 06/06/18 - Maize Field PM

- 08/06/18 - Maize Field PM

- 09/06/18 - Maize Field AM

- 09/06/18 - Maize Field PM

- 12/06/18 - Maize Field PM

- 13/06/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/06/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 22/06/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/06/18 - Didmarton Meet PM

- 23/06/18 - Didmarton Meet AM

- 25/06/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 26/06/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 05/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/07/18 - Cheddar Rugby Club AM

- 07/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- Balloon Flight | 08/07/18 - Maize Field AM

- 08/07/18 - South Gloucestershire PM

- 08/07/18 - Maize Field PM

- 10/07/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 11/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 16/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 17/07/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 18/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 18/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 19/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/07/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 22/07/18 - Keynsham AM

- 22/07/18 - Timsbury Flyout PM

- 25/07/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 02/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/08/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 09/08/18 - Pre Fiesta Flight | Ashton Court AM

- 21/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 28/08/18 - Bishop Sutton Flyout PM

- 30/08/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/08/18 - Maize Field PM

- 01/09/18 - Henbury AM

- 01/09/18 - Maize Field PM

- 02/09/18 - Tethering in Nailsea PM

- 02/09/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/09/18 - Maize Field PM

- 06/09/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 07/09/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 12/09/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/09/18 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/09/18 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 26/09/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/09/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/10/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/10/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 19/10/18 - Maize Field PM

- 20/10/18 - Ashton Court PM

- 28/12/18 - Maize Field PM

-

2017 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 05/01/17 - Cash4Cars over Bristol

- 22/01/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 18/02/17 - Ashton Court G-GAGE Tether

- 13/03/17 - Ashton Court AM

- Balloon Flight | 27/03/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 02/04/17 - Keynsham AM

- 02/04/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 05/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 05/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 06/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 06/04/17 - Maize Field PM

- 07/04/17 - Maize Field AM

- 07/04/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 08/04/17 - Maize Field AM

- 08/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 10/04/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 13/04/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 17/04/17 - Maize Field PM

- 18/04/17 - Keynsham PM

- 19/04/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 22/04/17 - Maize Field PM

- 23/04/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 27/04/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/04/17 - Ashton Court PM

- Balloon Flight in G-UWEB | 29/04/17 - Maize Field AM

- 06/05/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 07/05/17 - Maize Field AM

- 07/05/17 - Maize Field PM

- 09/05/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 10/05/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 24/05/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- Balloon Flight in Red Letter Days | 25/05/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 28/05/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 28/05/17 - Maize Field AM

- 31/05/17 - Ashton Court Tether PM

- 13/06/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/06/17 - Keynsham PM

- 14/06/17 - Maize Field PM

- 14/06/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/06/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/06/17 - Keynsham AM

- 18/06/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 18/06/17 - Tethering Bagerline - Ashton Court PM

- 19/06/17 - Maize Field PM

- 26/06/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 02/07/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/07/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/07/17 - Fiesta Charity Partnership Launch | Ashton Court PM

- 05/07/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 08/07/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 09/07/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 09/07/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 10/07/17 - College Green Tether AM

- 12/07/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 12/07/17 - Maize Field PM

- 17/07/17 - Maize Field AM

- 17/07/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 24/07/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 25/07/17 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 25/07/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/07/17 - Visit Bath Tether | Royal Crescent PM

- 01/08/17 - Ashton Court AM

- Balloon Flight in Tango | 06/08/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 20/08/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 24/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 27/08/17 - Ashton Court AM

- 27/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 28/08/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/09/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/09/17 - Bower Ashton PM

- 02/09/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/09/17 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/09/17 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 08/10/17 - Ashton Court PM

-

2016 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 16/01/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 11/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 12/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 13/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 18/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 20/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 21/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 22/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM & Ashton Court PM

- 23/03/16 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 25/03/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/03/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 17/04/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 17/04/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 28/04/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/04/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 03/05/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 05/05/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 06/05/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 14/05/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 14/05/16 - Maize Field PM

- 15/05/16 - Keynsham AM

- 22/05/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/06/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 18/06/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/06/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/06/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 27/06/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 03/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 04/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/07/16 - Balloons over Bristol PM

- 14/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 17/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/07/16 - College Green & Ashton Court PM

- 18/07/16 - Maize Field PM

- 23/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 23/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/07/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/07/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 06/08/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 17/08/16 - Maize Field PM

- 26/08/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/08/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 29/08/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 30/08/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/08/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/08/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 14/09/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 18/09/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/09/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 20/09/16 - Maize Field PM

- 23/09/16 - Ashton Court AM

- 02/10/16 - Ashton Court PM

- 08/10/16 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 27/12/16 - Ashton Court AM

-

2015 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 18/06/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 19/06/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 19/06/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/06/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 24/06/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/06/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/06/15 - Keynsham Rugby Football Club PM

- 27/06/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/06/15 - Maize Field, Royal Victoria Park & Keynsham Rugby Football Club PM

- 02/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/07/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/07/15 - Didmarton Flyout PM

- 05/07/15 - Didmarton Flyout AM

- 09/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 18/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 19/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 23/07/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/07/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/08/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 15/08/15 - Lloyds Amphitheatre AM

- 16/08/15 - Wickwar AM

- 16/08/15 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 16/08/15 - Maize Field PM

- 06/09/15 - Maize Field AM

- 06/09/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 07/09/15 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 17/09/15 - Ashton Gate Stadium PM

- 19/09/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/09/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/09/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/09/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/09/15 - Royal Victoria Park AM

- 02/10/15 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 18/10/15 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 20/10/15 - Ashton Court PM

- 25/10/15 - Ashton Court AM

- 25/10/15 - Keynsham RFC PM

-

2014 Bristol & Bath Flights

>

- 01/03/14 - Maize Field AM

- 05/03/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 09/03/14 - Lloyds Amphitheatre AM

- 01/04/14 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 04/04/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 09/04/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 10/04/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 11/04/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/04/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 13/04/14 - Shirehampton AM

- 14/05/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/05/14 - G-BPGD Landing

- 16/05/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 17/05/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 17/05/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/05/14 - Shirehampton PM

- 01/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 03/06/14 - G-VBAE over Bristol

- 05/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 11/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 12/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 15/06/14 - Timsbury Flyout PM

- 20/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 21/06/14 - Maize Field AM

- 21/06/14 - Maize Field PM

- 22/06/14 - Maize Field + RVP AM

- 22/06/14 - Bishop Sutton Flyout PM

- 24/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 29/06/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 30/06/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 01/07/14 - Keynsham RFC PM

- 02/07/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 06/07/14 - WRBBAC Flyout AM

- 15/07/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 20/07/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 21/07/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 30/07/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 04/08/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 20/08/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 31/08/14 - Ashton Court AM

- 31/08/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 01/09/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 02/09/14 - Royal Victoria Park PM

- 07/09/14 - Maize Field PM

- 21/09/14 - Queen Square AM

- 22/09/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 26/09/14 - Ashton Court PM

- 06/12/14 - Ashton Court AM

- Other 2014 Photos

- 2013 Bristol & Bath Flights >

- Fiesta Programmes >

- Bath Balloon Fiesta

- Midlands Air Festival >

- Longleat Sky Safari >

- Telford Balloon Fiesta 2022

- Telford Balloon Fiesta 2021

- Icicle Refrozen Balloon Meet 2020

- Icicle Refrozen Balloon Meet 2019

- Yorkshire Balloon Fiesta 2022

-

Other Events

>

- Berkshire Balloon & Action Extravaganza 2022

- Cheltenham Balloon Fiesta 2022

- Springkle Balloon Meet 2022

- Streatley Night Glow 2021

- Abingdon Firework Festival 2019

- Wales Airshow Night Glow 2019

- Balloons on the Beach | Weston-super-Mare 2019

- Balloons on the Beach | Weston-super-Mare 2018

- BBM&L Inflation Days

- Tiverton Balloon Festival 2015

- Queens Cup Balloon Race 2013

- Fiesta Newspapers

- More Photos

-

Bristol Balloon Fiesta

>

- Blog

- Contact

- Online Shop